The Availability Heuristic¶

Mathilda Kitzmann & John Mistele

“Who should I vote for?”, “Is it gonna rain later? Should I carry an umbrella with me?”, “What should I invest into?”

We act based on more or less serious decisions every day. With our beliefs about uncertain events and our personal assessment of ambiguous situations we take shortcuts for choosing quickly all the time. Our brain uses a limited number of heuristic principles to reduce complex judgments and ease decision making. These heuristics can be useful and quick, as we cannot analyze and research every small decision in our lives. At the same time, shortcuts make us susceptible to personal biases and influences. These can limit our neutral perspective and lead to “severe and systematic errors” (Tversky and Kahnemann, 1974, 1124).

This chapter explores the often-applied availability heuristic. It is the cognitive decision rule through which people judge probability and frequency of an event or classification by availability, i.e. the “ease with which relevant instances come to mind” (Tversky and Kahnemann, 1973, 207). Availability heuristics can lead to easier and quicker decisions, but can also result in biased and incorrect judgements. This cognitive decision rule was first labeled by researchers in psychology Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahnemann, who examined human heuristics and biases in a series of papers. In this series they introduced the cognitive shortcuts humans make through an assessment of availability across ten experiments. Kahnemann and Tversky are groundbreaking researchers of cognitive heuristics in decision making. Their pioneering role in the field of judgement and decision making led to Kahnemann winning the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002, 6 years after Amos Tversky’s death.

We will look at the psychological approach to the availability heuristic and its corresponding bias. Examples will be given for impairments of the cognitive decision strategy an intuitionally lacking interest in source reliability, media’s influence, and mistakes in perceived risk. Furthermore, we will discuss a critique about our experience influencing the heurisitc itself.

Discovering the Availability Heuristic¶

The foundational studies on the Availability Heuristic were performed by Tversky and Kahneman, published in 1973 around the time of some of Tversky and Kahneman’s other work on cognitive biases. Tversky and Kahneman first showed that subjects are able to accurately assess the quantity of examples they could recall or construct (the “available” examples) in much less time than it took them to actually recall or construct those examples. Thus, assessments of availability are cheap and accurate enough to be useful, assuming availability is truly a good proxy for the real frequency or quantity of examples.

Thus the intriguing cases are where availability fails as a proxy, yet humans still seem to use availability as the grounds for their frequency and quantity estimates yielding predictable errors. The following passages will summarize three such classes of tasks.

The first class of estimation tasks where the availability heuristic led subjects astray involved mental construction. Subjects were given the task of estimating how many ways a two-person subcommittee could be chosen from a group of ten people, then given the task of estimating how many ways an eight-person subcommittee could be chosen from a group of ten people. Any two-person subcommittee corresponds to exactly one eight-person subcommittee of all the people who were previously excluded, so that these two quantities are mathematically identical. Despite this, respondents systematically gave larger answers for the number of possible two-person subcommittees than for the number of eight-person subcommittees. Two-person subcommittees are much easier to imagine; they somehow take up less mental space, so that such subcommittees feel more available and thus more frequent than their eight-person counterparts.

The second class of tasks where availability distorts estimates involves salience. Subjects in two groups were given two lists of names, one of twenty less famous men and nineteen famous women, and one of twenty less famous women and nineteen famous men. One group was asked to recall as many names as they could; on average, 12.3 of 19 famous names were recalled and only 8.4 of 20 less famous names were recalled. The other group was asked to estimate the relative frequency of the genders in each list; 80 of 99 study participants erroneously asserted that the class consisting of the more famous names was more frequent. Thus, the more salient famous examples were more easily recalled, i.e. available, leading to an erroneous judgement of frequency.

The third class of frequency estimation error lies in distortions of the search mechanism used. Kahneman and Tversky asked participants to judge the relative frequency of words in English with R as the first letter vs. R as the third letter. Despite R being more common as a third letter, more than two thirds of participants responded that R is more common as a first letter than as a third letter. The same effect was observed for K, L, N, and V. This can be explained by the availability of lexicographic orderings of words and the weight we place on first letters; when probing the mind for words beginning with R, for many it is clear where to look, as they have already been grouped. Not so for third letters; thus the less available example is erroneously judged as less frequent.

Why and how Availability Heuristics Lead to Errors¶

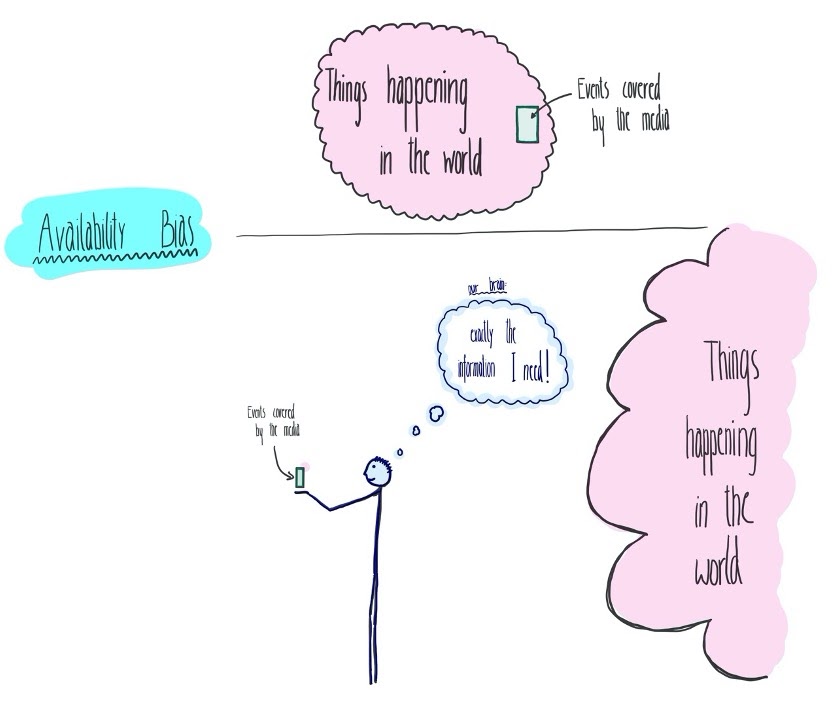

*Fig 1: Sketched model of a person judging a

situation by the information hey can

easily retrieve, here what they are presented by media.

*Fig 1: Sketched model of a person judging a

situation by the information hey can

easily retrieve, here what they are presented by media.

Heuristics do not care about source reliability¶

Imagination of an event alone has an effect on our perception of reality. Due to availability bias, simply imagining an event already leads to an increase in our “subjective likelihood” (Carroll, 1978) for its occurrence. While availability heuristics rely on our memory for forming an opinion about frequency, that is also the part where our judgement is most susceptible to errors, shortcuts and bias. This interference in our probability judgement even occurs as we are confronted with hypothetical or even obviously nonexistent events.

In 1978 John Carroll published a study with two experiments showing that imagining an event could, in itself, sufficiently lead to a person to later judge it to be more likely. Carrol refers to work by Neisser from the same year, who proposed similarities in psychological processes between the activity of the brain imagining an object and directly seeing an object. In both mechanisms, an “anticipatory schema” modifies information and expectations, and samples the given input related to the object. In his work, Carroll let participants imagine the event of either Ford or Carter winning the 1976 Presidential Election. In a second experiment participating students from the University of Pittsburgh were asked to imagine a good or bad season for their university’s football team. The participants were fully aware it was a highly hypothetical scenario. After imagining the given situation, the first experiment’s participants were asked which candidate they see to be more likely to eventually win the election. For the second experiment the participants evaluated first whether they thought that the football season of the given team was going to be a “good” one and secondly, they were asked to give predictions for a postseason bowl bid. The instructions to imagine a specific event increased the expectation for the imagined outcome in reality.

Impact of the media¶

Information presented by the media influences our evaluation of salience. It keeps events present, and therefore changes our perception of recency, all factors on which our assessment of availability depends. Even advertising takes advantage of the availability bias. It does not matter if we may not like the way a specific product is promoted or might even perceive it sometimes as annoying. Still, advertisements – even annoying advertisements for products we dislike – serve the role of announcing the existence of a product. Problems about which we were unaware become visible through ads. The next time we buy something, we can see ourselves confronted with a problem we have an easily available solution for, due to what we read, saw, or heard before. Additionally, media has a high influence on imaginability. As discussed in the previous section, events that are presented to us, even only hypothetically, can change our perceived likelihood of them actually happening.

According to cultivation theory, one of the most prominent mass communication models, people see their social reality as more congruent with the reality presented by television, as they spend more time consuming TV (Potter and Riddle cited by Riddle 156). On a cognitive level, availability heuristics can explain this effect. With a more often and recent exposure to television, we construct easily accessible and relatable memory and connections to possible events and occurrences. Multiple studies see a clear correlation between the amount of TV watched and its impact on accessibility.

Research by Karyn Riddle (2010) has investigated the influence of TV on social reality judgement. Participants were assigned to watch a specific television program. The exposure to violent programs differed between the groups of participating students in frequency, recency, and vividness. Frequency and vividness had a strong influence on the participants’ social beliefs. In the groups with the highest exposure to vivid violent programs, the estimates of crime and police immorality increased significantly. The study shows that the process of constructing judgements about the frequency of crime and violence in society can be influenced by the TV programs we are exposed to. In this way media strongly influences our perception, an effect that can be seen in many more aspects of our lives than the impact on social beliefs.

Perceived Risk¶

Pioneering research on people’s perception of risks was conducted by Paul Slovic and Sarah Lichtenstein in 1985. They conducted a survey in which participants were asked to judge which of two causes of death were more frequent. Results of the study are also presented in Daniel Kahnemann’s book Thinking Fast and Slow. In Slovic and Lichtenstein’s study, 80% of participants judged accidental death as more likely than strokes, even though strokes actually cause twice as many deaths. Tornadoes were seen as a more frequent cause of death than asthma, although death by asthma is 20 times as likely. Even though death by disease is 18 times as likely as accidental death, these two were considered to be about equally likely. Death by accidents was also judged to be more than 300 times more likely than death by diabetes, even though four times as many people die from diabetes than they do by accidents. The study and its results are now widely considered as a “standard example of an availability bias” (Slovic and Liechtenstein, 1985, cited by Kahnemann 138).

These evaluations clearly show how estimates of deaths are influenced by media coverage. At the same time, the media do not shape what the public is interested in. Rather, the media are biased toward the public demand for “novelty and poignancy” (Kahnemann 138). Unusual events attract more attention than reports of people dying of heart disease, asthma, or diabetes. Our expectations about the frequency of occurrences are distorted by prevalence and emotional intensity.

Availability biases can also directly help to explain the increase in insurance purchase and protective action after disaster. Kahnemann explains behaviors discovered by Howard Kunreuther in research of risk and insurance. After significant earthquakes, people in California tend to purchase insurance and adopt measures of protection in way higher rates. For example, they tie down their boiler to reduce a possible damage by an earthquake and maintain emergency supplies (Kahnemann 137). However, the memories become less present over time. Retrievability, time of occurrence and salience become less clear.

As we see, images of events in the past and our available memories of them shape our expectations of the future. In this way individuals and even governments often design protective actions adequate to the worst experienced disaster. Already in pharaonic Egypt, societies tracked the high-water mark of floods to be prepared for the assumedly worst possible case (Kahnemann 137). The same still seems to be true for our modern methods of managing safety measurements against floods. Tversky and Kahnemann cite in their 1973 published paper the work by Robert Kates (1962), who pointed out a basic reliance on experience to be a major limitation to use improved flood hazard information. Furthermore he writes, “Recently experienced floods appear to set an upper bound to the size of loss with which managers believe they ought to be concerned.” (Kates 140 cited by Kahnemann and Tversky, Availability, 230). As Kates argues, inability of individuals to imagine floods unlike any that have occurred is a main restriction on efficient prevention of destruction by flood.

People’s assessment of availability is highly susceptible to shortcuts, errors, and biases. As discussed above, the fact that we heard, read, or generally perceived something before, makes it appear to us to happen more likely. It highlights the risk of bias by intense consumption of television or even fake news or hypothetical events. Perceiving these can change our assessment of frequency, likelihood, and finally influence our decision making. A high perceived risk of events, which are actually only low danger, such as chances of different causes of death, can shift our focus to be overcautious for rationally unreasonable events.

Critique of the Heuristic: Experienced Ease of Recall Dominates Availability¶

While Kahneman and Tversky proposed that the availability of examples is used as a means of determining the frequency of those examples, Schwarz et al (1991) point out that Kahneman and Tversky did not thoroughly investigate the mechanism by which availability operates. To interrogate this, the following study was conducted.

Schwarz et al asked two groups of subjects tho recall either N = 6 or N = 12 examples of times they were assertive. In this way, the subjects should have easily available examples of times they were assertive, and as such we might anticipate that those who generated twelve examples will rate themselves as more assertive than the six-example group. However, Schwarz et al observed instead that, in fact, it is the N = 6 group which considers itself more assertive; most subjects find it difficult to generate more than eight or so examples, and by subjecting the twelve-example group to the task of exceeding this number, their available examples, while more available, are colored by the relative difficulty with which they were attained. They rate themselves as less assertive. Thus, Schwarz et al demonstrate a context where experienced ease of recall, not availability, drives intuitive estimates of frequency, critiquing and refining the Kahneman and Tversky findings.

References¶

Carroll, John (1978). The effect of imagining an event on expectations for the event: An interpretation in terms of the availability heuristic. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 14 (1): 88–96.

Gabrielcik, A., & Fazio, R. H. (1984). Priming and Frequency Estimation: A Strict Test of the Availability Heuristic. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 10(1), 85–89.

Kahneman, Daniel (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow.

Riddle, Karyn (2010). “Always on My Mind: Exploring How Frequent, Recent, and Vivid Television Portrayals Are Used in the Formation of Social Reality Judgments”. Media Psychology. 13 (2): 155–179.

Schwarz, N. et al. (1991). “Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(2), 195–202.

Tversky, Amon; Kahnemann, Daniel. “Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability” Cognitive Psychology, Volume 5, Issue 2, 1973, 207-232

Tversky, Amon; Kahnemann, Daniel. “Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases”. Science, Vol. 185, issue 4157, 1974, 1124-1131

Wänke, Michaela, et al. (1995). “The availability heuristic revisited: Experienced ease of retrieval in mundane frequency estimates”. Acta Psychologica, Volume 89, Issue 1, 83-90.